The film is in black and white. A ship is docking at an unknown port. Men line the rail of the vessel, looking down uncertainly at the men and women waiting along the wharf. They are smartly dressed in suits, shirts and hats redolent of the 1950s. There’s a sense of excitement, of arrival at a longed for destination. Those on board ship call down to those on shore, who smile and wave back at them. One of the men on the ship, a tough-looking guy in a light-coloured suit, consults a piece of paper; he confers with a couple of other men, apparently unsure what to do. Then, the camera – which has been roving democratically over the crowd on shore – picks out a neatly-dressed old man, in suit, hat and glasses. The young man has seen him too. His look of doubt changes to one of joyful recognition, and we see his lips move: “Papa!” He runs down the gangway; they embrace.

It’s a vivid and moving scene, filmed in a realist or documentary style, made even more effective by the fact that it is played out in silence. The ship, the crowds, the speech and the action are completely inaudible. The film is mute.

Watch the clip here: http://aso.gov.au/titles/features/il-contratto/clip1/

*

It’s September 2015, the day before the AFL Grand Final, and I’m sitting in an Italian cafe – established 1952 – in Lygon Street, Carlton, with Ettore Siracusa. Ettore is a film-maker and film historian who has invited me for coffee to discuss the work of Giorgio Mangiamele, one of Australia’s most interesting post-war film-makers.

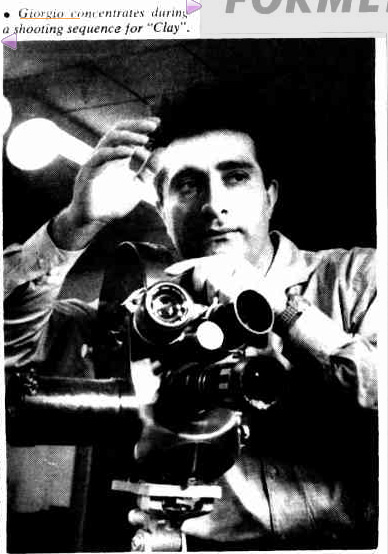

Ettore, now in his 70s, was a migrant to Melbourne from Sicily. Ettore arrived in 1956, and enrolled in the New Continent Film and TV School in Russell Street, which taught acting and TV production skills. Here he met Mangiamele – “Let’s call him G.M.” – also a migrant from Sicily, who had preceded him to Australia by several years. Starting out as an actor in films made as part of the curriculum, Ettore became G.M.’s cameraman and assistant director on subsequent projects, including G.M.’s most well-known film, Clay.

But we must backtrack a little. Years before that, in 1953, G.M. had set out to make his first feature film, titled Il Contratto (The Contract). Despite the fact that he had no finance, and had barely been in Australia for a year, G.M. decided to record his experiences on celluloid. Laughing, Ettore tells me: “So this enterprising G.M., just off the ship, says ‘Let’s make a film’!”

G.M. acted as well as scripting and directing, and called on his friends – non-professional actors – to fill the other roles. For a storyline he drew on the experiences of Italian migrants like himself, lured to Melbourne by promises of work contained in ‘the contract’ of the film’s title. The characters walked the streets of Carlton and Melbourne – landmarks such as Flinders Street station are visible – applied for jobs, were rejected, encountered racism – experiences shared by many of the thousands of Italians who migrated to Melbourne after the war, many of them to Carlton.

All this can be seen in the film. In silence.

*

Four young men are strolling along Lygon Street in conversation. Just past the Carlton Community Chemist, near the Faraday Street intersection, they stop to pick up a newspaper, which they impatiently divide between them. The Albion Hotel can be seen briefly in the background. They find something in the paper – look boys, a vacancy, men wanted! – and rush off, leaping onto a classic W-class tram. Outside a factory, they join a queue of anxious men. There’s some kind of dispute; a fight almost breaks out. (The amateur actors do their best, but the action is, it must be said, a touch unconvincing). The young Anglo bloke calling the men out of the queue suddenly makes an announcement, waves them away and closes the door. The four trudge gloomily off.

Watch the clip here: http://aso.gov.au/titles/features/il-contratto/clip2/

*

The post-war era was not a promising time to be a film-maker in Australia. The Australian Screen website lists only nine Australian feature films from the 1950s, far fewer than the 1930s. Most feature films made in Australia at that time involved foreign directors and actors. As for films about the migrant experience, the first to achieve commercial success was They’re A Weird Mob (1966) directed by the Englishman Michael Powell 13 years after Mangiamele began his career.

The young G.M. had remarkable self-belief and a desire to tell authentic stories.”He intended the film for the Italian market,” Ettore explains. “He wanted to subvert the idea of ‘the contract’ which had brought many Italians to Australia. But he could never complete it.”

G.M.’s intention was to shoot Il Contratto first, then add the soundtrack in post-production – the usual practice of Italian film-makers. But at the time there was no facility in Melbourne where G.M. could dub the sound. As time passed, the project went on to the back-burner, and the soundtrack was never added. The film was not commercially shown in G.M.’s lifetime and to this day it remains incomplete, its actors and scenes poignantly silent.

We are accustomed to the ‘silent’ films of an earlier era, which were not truly silent, because there was a musical accompaniment; the action in such films was explained by elaborate mime and title cards. There is none of this in Il Contratto, making the silence all the more profound. Much of the dialogue can only be guessed at; some of the action is ambiguous or inexplicable; the dialogue cannot be decoded with certainty even by Italian lip-readers. What G.M. really wanted us to hear is unknown and lost.

*

Now the four guys have found work on a farm in Werribee. As they toil in a field of vegetables, we see various scenes that display their unsuitability for agricultural life. One guy wields a shovel, ineptly; two others struggle comically to lift a pile of boxes. But the situation has improved in one way: they’ve been joined by a pretty girl. She is seen laughing as she tries to feed a goose, then she chases it, skirt flying. Clearly, she will be the romantic interest. There’s a naturalness to her presence that lights up the screen.

Watch the clip here: http://aso.gov.au/titles/features/il-contratto/clip3/

*

Although he never completed Il Contratto, G.M. was not deterred from making more films. His most noted feature was Clay (1964), a very different film, lyrical and enigmatic, full of symbolism, about a man on the run who hides out at Montsalvat artists colony. G.M. had to mortgage his own house and photographic studio to make it.

Still with no lack of self-confidence, he submitted the film to Cannes Film Festival, where it screened in competition in 1965. Ettore, who accompanied G.M. to Cannes, refuses to be drawn on the experience of the world’s most glamorous film festival: he smiles discreetly as he hints that story is yet to be told. Whatever happened, Cannes was a long way from Werribee.

Clay earned good reviews from international newspapers, but failed to be released commercially in Australia. G.M. – “full of grandeur and ambition”, says Ettore wryly – hired a 2000-seater cinema – the Palais in St Kilda – for the film’s only season, but the audience was disappointing. After this let-down, G.M. only made one more feature – Beyond Reason, which failed critically and commercially.

In the late 60s and early 70s, Australian cultural life – and cinema – underwent a rebirth. The example of G.M. was cited by figures like Tim Burstall, Philip Adams and Barry Jones, who campaigned for government support for the film industry. “He was a significant figure, a protagonist in the movement to get the film industry off the ground,” Ettore tells me. But as the industry began to take off, making household names of the likes of Peter Weir, G.M. remained an outsider. Determined to make art films rather than commercial movies, he rarely gained any funding himself, instead making a living from his photographic studio on Rathdowne Street.

“He never gave up wanting to make films,” Ettore tells me. “He became ‘G.M’ who was – but he still wanted to be an is.” Scripts and treatments piled up in his studio – the raw materials of what Ettore calls “G.M.’s unmade private cinema”. A disappointed man, he died in 2003.

*

It’s a story of absences and incompleteness – a little-known director, unseen or unmade films, a permanent outsider. Histories of Australian film don’t accord him much of a place, despite his pioneering work. Was G.M., like one of the characters in Il Contratto, looking to make it in a country where the odds were stacked against him? Or was his the familiar story of the visionary who refuses to compromise and remains in obscurity? Is that the true contract that history offers some artists: you can have genius, but no one will recognise it? The incomplete Il Contratto, lacking its soundtrack, seems a perfect metaphor for the career of its maker.

*

Long after it was made, there was renewed interest in Il Contratto and Mangiamele. The film was used in a Museum Victoria exhibit of ‘The Jews and Italians of Carlton’ in 1988. It had become a part of history, a nostalgic look back at the Carlton of the 1950s with its butcher’s shops and espresso bars. After G.M.’s death, at Ettore’s urging the film was accepted by the National Film and Sound Archive; critical works began to appear. Now Ettore has another project in mind, hoping to bring the film to a new audience.

A few years ago Ettore tried to find the actors who had appeared in Il Contratto. He discovered they were all dead, apart from one – the woman who had played Claudia, the girl on the farm. Her name was Halina Kisilevski, and she had left Australia in 1964 to move to New York. Amazingly, Ettore tracked her down on a brief return visit to Melbourne to ask her about her part in a piece of Australian film history. And what did she say?

“Nothing. She didn’t remember a thing about it.”

*

These days, the old Albion Hotel is a fashion store; but the community chemist is still a chemist. Some things have changed, but much remains that G.M. would have recognised, including the cafe where I am sitting with Ettore, which contains a vintage coffee machine in a glass case. The smell of coffee wafting down Lygon Street is the same, there are still knots of men and women intent in Italian conversation. You can imagine seeing four young men in suits and ties, hair quiffed in the fashion of the 50s, walking briskly along the street, gazing intently at a newspaper. Thanks to G.M., of all the thousands who came to Melbourne at that time, their image survives. And somewhere out on the farm, there’s a pretty girl gathering a goose against her skirt.

*

Notes on Il Contratto from Australian Screen

Biographical notes on Mangiamele from Australian Screen

The Giorgio Mangiamele Collection trailer on Youtube

‘Giorgio Mangiamele’s Clay and the beginnings of art cinema in Australia‘: an academic article on Mangiamele’s work by Gino Moliterno, in particular Clay, with stills from that film and a discussion of G.M.’s influences.